CEEMID

CEEMID (2014-2020) is now the Digital Music Observatory

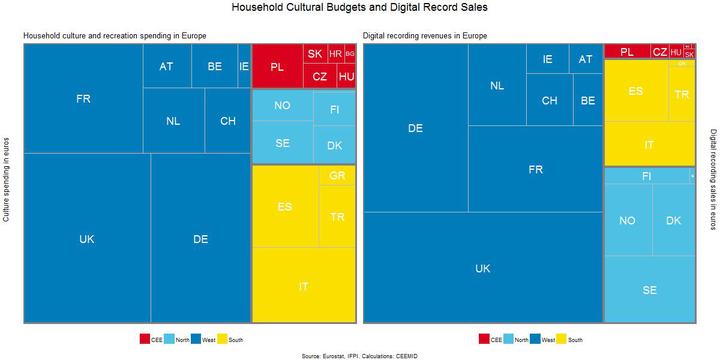

The Feasibility study for the establishment of a European Music Observatory (in short: EMO Feasibility Study)[1] has identified four critical data gaps related to the diversity and circulation of European music. This is a key business planning and policy problem, and of course, a serious shortcoming for better music research in Europe.

According to the EMO Feasibility Study, “there is already an existing pool of data that would allow the European Music Observatory to start compiling information about the European music sector. Various potential sources and providers of data are … [available, such as our Digital Music Observatory.]. Many of these providers have already indicated support for a future European Music Observatory, and are willing to collaborate and provide data. However, some data is not collected or is not aggregated in a way that it can be compared across Europe[2].

From CEEMID to the Digital Music Observatory

The Digital Music Observatory (formerly CEEMID) has been identified among these data sources[3]. CEEMID was originally an acronym for a data integration project that aimed to Create a Regional Music Database to Support Professional National Reporting, Economic Valuation and a Regional Music Study[4]. According to the European Commission’s feasibility study, “CEEMID can transfer thousands of indicators that are reproducible and verifiable, open-source software that creates them to a European Music Observatory. In particular, CEEMID provides a useful and interesting approach to harnessing the possibilities of open data in Europe in relation to the music sector, which should be further explored by the European Music Observatory in its start-up phase.”[5]

The Digital Music Observatory is built on the gradual, and open extension of the original CEEMID consortium, and builds on practical research and innovation that contributed to many music policy goals in an increasing number of countries since 2014. The original CEEMID consortium delivered the first Hungarian music industry studies (followed by several subsequent ones), the Slovak national music industry study, Private Copying in Croatia, and eventually the regional Central European Music Industry Report.[6] All of these industry studies addressed the problem of shrinking competitiveness in of the small language repertoire in the streaming era.

The EMO Feasibility Study is built on the consensus of many European music organizations around a shared understanding “that a European Music Observatory should act as a centralised music data and an intelligence hub at European level.” However, as a pilot project and policy brief carried out in Finland[7], or the CEEMID project in Central and Eastern Europe has shown, has its limits. We believe that the existing data availability is better than that described in the Feasibility study, and since the creation of this report, it has only got better.

Since 2014, the Digital Music Observatory (former CEEMID) successfully piloted data collection, standardization and harmonization procedures that can fill all the data gaps identified in the music diversity and circulation pillar of the future European Music Observatory. CEEMID was transformed into a “Demo Music Observatory” on 15 September 2020[8] and eventually named Digital Music Observatory in 2021. Its policy relevance was also recognized in the United Kingdom after Brexit[9].

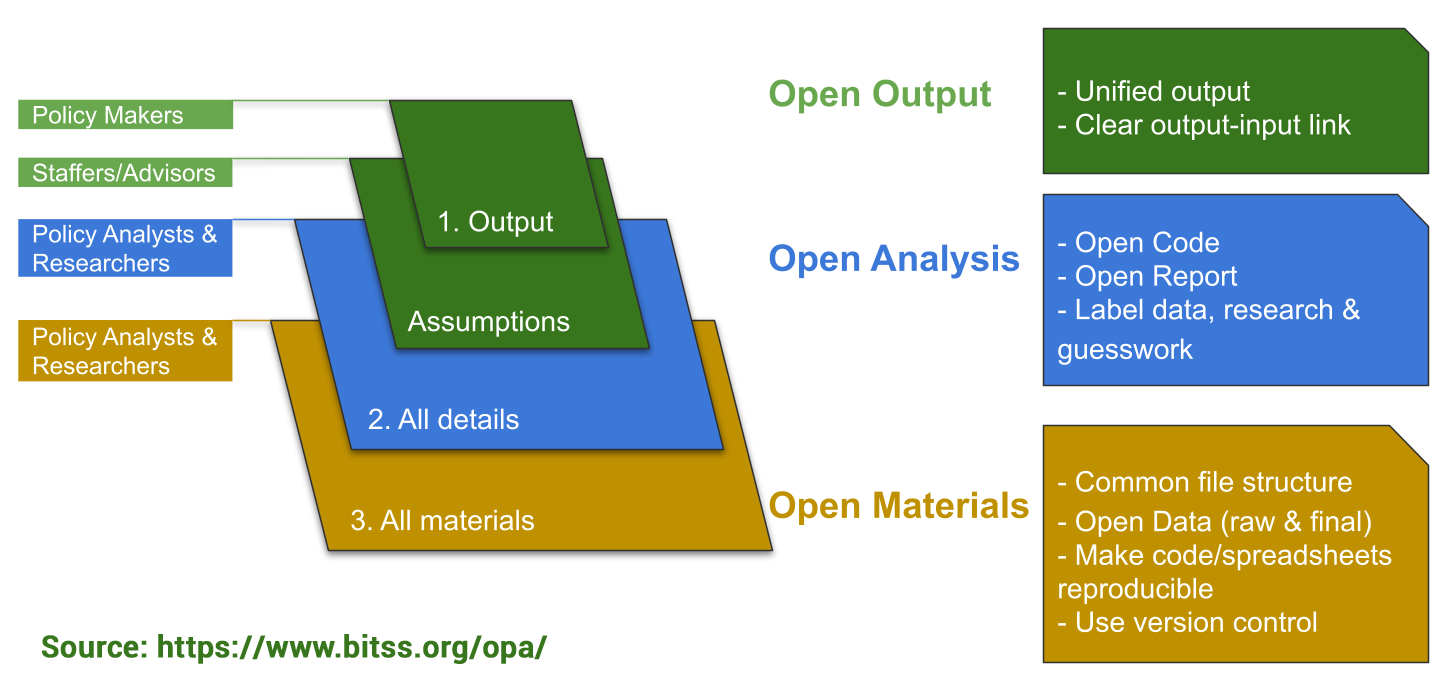

The Digital Music Observatory follows the Open Policy Analysis Guidelines[10] The OPA Guidelines give practical guidance on how to improve the transparency, replicability, and as a result, the reusability of the policy-making work with a scientific underpinning.

The EMO Feasibility Study acknowledges the importance of open data. The “EMO should also take advantage of open data where possible. Open data is data that can be freely used, re-used and redistributed by anyone. […] Using some form of open source software where relevant would allow an EMO to access a continuous peer-review of data ingestion, processing, corrections and indicator creation by statisticians, data scientists and academics.”[11]

As stated in this final report, the 2019 Open Data Directive further extended the availability of re-usable public sector information (PSI) with open science data. . In both PSI, as open government data, and in open science data, there is a huge potential to fill in the data gaps without new data collection—the fact that data can be reused instead of being recollected is the main aim of the directive. However, open data does not mean public data. Open data means that taxpayer-funded research data can be repurposed, reprocessed, and reused—the Digital Music Observatory is an expert on such data science techniques.

The Digital Music Observatory is not an alternative to the future European Music Observatory, just its open source, open data driven voluntary, based on open collaboration with music industry stakeholders, music policy makers and users, academic researchers, individual and citizen scientists, and individual artists. Because we create fully automated research tools that are creating open datasets, and open source software, even our research infrastructure can be fully transferred to a future European Music Observatory[12].

We are not planning to make a competing data observatory. We want to provide a minimum viable model of creating at least a hundred useful indicators—selected from hundreds of indicator-candidates with user feedback— that goes through the unit-testing of data science and computer science, the peer-review of open-source scientific algorithm/software development, the methodological peer-review of science, and eventually user verification from music industry users. This will make sure that the indicators can be reproduced, refreshed, and placed in a future European Music Observatory with at least as good data quality as one would expect from a governmental statistical source or Eurostat.

The aim of the Digital Music Observatory is to maximize transparency by introducing to the policy context of Music Moves Europe, and the wider European music ecosystem the Open Policy Analysis framework. (See Open Collaboration, Open Policy Analysis, and Open Data.)

Open Collaboration, Open Policy Analysis, and Open Data

We aim to maximize transparency by introducing to the policy context of Music Moves Europe, and the wider European music ecosystem the Open Policy Analysis framework. (BITSS 2019; Hoces de la Guardia, Grant, and Miguel 2020b).

Our policy tools will make possible the first, large scale European application of the Open Policy Analysis, which grew out from several initiatives in research transparency, such as the Berkeley Initiative for Transparency in the Social Sciences, the Data Access and Research Transparency (DA-RT) group, the Center for Open Science and their TOP Guideline, the Meta-Research Innovation Center at Stanford University. Globally, the World Bank promotes this framework (Hoces de la Guardia, Grant, and Miguel 2020b; Berkeley Initiative for Transparency in the Social Sciences et al. 2020) and they are fully in line with the Open Science objectives of the European Union (Commission et al. 2020).

We believe that existing data availability is better than that described in the Feasibility study. As stated in this final report, the 2019 Open Data Directive further extended the availability of re-usable public sector information (PSI) with open science data. In both PSI, as open government data, and in open science data, there is a huge potential to fill in the data gaps without new data collection—the fact that data can be reused instead of being recollected is the main aim of the directive. These open data sources are legally open but are not accessible without further investment, and our Consortium wants to make this investment, and produce about 50% of all the data needs of the future European Music Observatory.

It also mentioned the work CEEMID, a bottom-up initiative originally started by three collective management societies, and eventually joined by more than 60 stakeholders in 12 European countries to fill in some of these gaps with a) voluntary data integration among partners b) open data re-processing c) co-financed data collection. Our proposal wants to put the former CEEMID, currently named Digital Music Observatory, a more solid scientific and methodological foundation, to make it more user-friendly, and to exploit state-of-art statistical, data science and computer science methods to provide more comprehensive, timely, and accurate services for the European music sector.

References

Antal, Daniel. 2015. “A Proart zeneipari jelentése. [The Music Industry Report of Proart].” ProArt Szövetség a Szerzői Jogokért Egyesület. http://zeneipar.info/letoltes/proart-zeneipari-jelentes-2015.pdf.

———. 2017. “The Growth of the Hungarian Popular Music Repertoire: Who Creates It And How Does It Find An Audience.” In Made in Hungary, 1st ed. Studies in Popular Music. New York, NY: USA: Routledge.

———. 2019a. “Private Copying in Croatia.” https://www.zamp.hr/uploads/documents/Studija_privatno_kopiranje_u_Hrvatskoj_DA_CEEMID.pdf.

———. 2019b. “Slovak Music Industry Report [Správa o slovenskom hudobnom priemysle].” https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/V3BE9.

———. 2020. “Central And Eastern European Music Industry Report 2020.” CEEMID, Consolidated Independent. https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.2.21450.31686.

Artisjus, HDS, SOZA, and Candole Partners. 2014. “Measuring and Reporting Regional Economic Value Added, National Income and Employment by the Music Industry in a Creative Industries Perspective. Memorandum of Understanding to Create a Regional Music Database to Support Professional National Reporting, Economic Valuation and a Regional Music Study.”

Berkeley Initiative for Transparency in the Social Sciences, Aleksandar Bogdanoski, Carson Christiano, Joel Ferguson, Fernando Hoces de la Guardia, Katherine Hoeberling, Edward Miguel, Emma Ng, and Lars Vilhuber. 2020. “Guide for Accelerating Computational Reproducibility in the Social Sciences.” Berkeley Initiative for Transparency in the Social Sciences. https://bitss.github.io/ACRE/intro.html.

BITSS. 2019. “Guidelines for Open Policy Analysis.” Berkeley Initiative for Transparency in the Social Sciences. http://www.bitss.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/OPA-Guidelines.pdf.

Commission, European, Directorate-General for Research, Innovation, L Baker, I Cristea, T Errington, K Jaśko, et al. 2020. Reproducibility of Scientific Results in the EU : Scoping Report. Edited by W Lusoli. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union. https://doi.org/doi/10.2777/341654.

EUR-Lex. 2019. “Directive (EU) 2019/790 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 17 April 2019 on Copyright and Related Rights in the Digital Single Market and Amending Directives 96/9/EC and 2001/29/EC (Text with EEA Relevance.).” Official Journal of the European Union OJ L (130): 92–125. http://data.europa.eu/eli/dir/2019/790/oj.

European Commission, Directorate-General for Education, Youth, Sport and Culture, M Clarke, P Vroonhof, J Snijders, A Le Gall, B Jacquemet, et al. 2020. Feasibility Study for the Establishment of a European Music Observatory : Final Report. Publications Office of the European Union. https://doi.org/doi/10.2766/9691.

Hoces de la Guardia, Fernando, Sean Grant, and Edward Miguel. 2020b. “A framework for open policy analysis.” Science and Public Policy 48 (2): 154–63. https://doi.org/10.1093/scipol/scaa067.

———. 2020a. “A framework for open policy analysis.” Science and Public Policy 48 (2): 154–63. https://doi.org/10.1093/scipol/scaa067.

Osimo, David, Pujol Priego Laya, Turo Pekari, and Ano Sirppiniemi. 2019. “A Symphony, Not a Solo. How Collective Management Organisations Can Embrace Innovation and Drive Data Sharing in the Music Industry.” Teosto. https://www.teosto.fi/app/uploads/2020/10/27134714/a-symphony-not-a-solo-policy-brief-final-09012019.pdf.

state51 Music Group. 2020. “Written Evidence Submitted by The state51 Music Group. Economics of Music Streaming Review. Response to Call for Evidence.” UK Parliament website. https://committees.parliament.uk/writtenevidence/15422/html/.

[1] Feasibility study for the establishment of a European Music Observatory (European Commission et al. 2020).

[2] Feasibility study for the establishment of a European Music Observatory (European Commission et al. 2020, pp31–34).

[3] Our observatory is mentioned to be ablet to participate with “data collection and integration system based on open data, opensources and online surveys” in all pillars of the future European Music Observatory, including Diversity & Circulation (European Commission et al. 2020, p40.)

[4] The original aim of CEEMID was Measuring and Reporting Regional Economic Value Added, National Income and Employment by the Music Industry in a Creative Industries Perspective Three national collective management societies and their consultant signed Memorandum of Understanding about this in 2014 (Artisjus et al. 2014).

[5] Feasibility study for the establishment of a European Music Observatory (European Commission et al. 2020, pp147–148).

[6] A ProArt zeneipari jelentése (Antal 2015) and The Growth of the Hungarian Popular Music Repertoire: Who Creates It And How Does It Find An Audience (Antal 2017); Správa o slovenskom hudobnom priemysle (Antal 2019b), Private copying in Croatia (Antal 2019a), Central Euroepan Music Industry Report (Antal 2020).

[7] See the Policy Brief A Symphony, not a Solo (Osimo et al. 2019).

[8] Antal-Szentirmay: Launching Our Demo Music Obervatory (blogpost)

[9] Written evidence submitted by The state51 Music Group. Economics of music streaming review. Response to call for evidence (state51 Music Group 2020).

[10] The Open Policy Analysis Guidelines which grew out from several initiatives in research transparency, such as the Berkeley Initiative for Transparency in the Social Sciences, the Data Access and Research Transparency (DA-RT) group, the Center for Open Science and their TOP Guideline, the Meta-Research Innovation Center at Stanford University (BITSS 2019; Hoces de la Guardia, Grant, and Miguel 2020a).

[11] In the EU, open data is governed by Directive (EU) 2019/1024 on open data and the re-use of public sector information (EUR-Lex 2019), which replaced the Public Sector Information Directive, also known as the ‘PSI Directive’ which dated from 2003 and was subsequently amended in 2013. Feasibility study for the establishment of a European Music Observatory (European Commission et al. 2020, p38).

[12] In other words, our aim, fully in line with the intentions of the Commission expert who were encouraging us to make this proposal, and with the Feasibility Study, is to create open source scientific/statistical software and pilot open data that can be utilized in 4/4 identified data gaps related to music diverstiy and circulation in the European Music Observatory.