Music Creators’ Earnings in the Streaming Era

United Kingdom Research Cooperation With the Digital Music Observatory

The idea of our Digital Music Observatory was brought to the UK policy debate on music streaming by the Written evidence submitted by The state51 Music Group to the Economics of music streaming review of the UK Parliaments' DCMS Committee1.

The music industry requires a permanent market monitoring facility to win fights in competition tribunals, because it is increasingly disputing revenues with the world’s biggest data owners. This was precisely the role of the former CEEMID2 program, which was initiated by a group of collective management societies. Starting with three relatively data-poor countries, where data pooling allowed rightsholders to increase revenues, the CEEMID data collection program was extended in 2019 to 12 countries.The final regional report, after the release of the detailed Hungarian, Slovak and Croatian reports of CEEMID was sponsored by Consolidated Independent (of the state51 music group.)

CEEMID was eventually to formed into the Demo Music Observatory in 20203, following the planned structure of the European Music Observatory, and validated in the world’s 2nd ranked university-backed incubator, the Yes!Delft AI+Blockchain Validation Lab. In 2021, under the final name Digital Music Observatory, it became open for any rightsholder or stakeholder organization or music research institute, and it is being launched with the help of the JUMP European Music Market Accelerator Programme which is co-funded by the Creative Europe Programme of the European Union.

In December 2020, we started investigating how the music observatory concept could be introduced in the UK, and how our data and analytical skills could be used in the Music Creators’ Earnings in the Streaming Era (in short: MCE) project, which is taking place paralell to the heated political debates around the DCMS inquiry. After the state51 music group gave permission for the UK Intellectual Property Office to reuse the data that was originally published as the experimental CEEMID-CI Streaming Volume and Revenue Indexes, we came to a cooperation agreement between the MCE Project and the Digital Music Observatory. We provided a detailed historical analysis and computer simulation for the MCE Project, and we will host all the data of the Music Creators’ Earnings Report in our observatory, hopefully no later than early July 2021.

We started our cooperation with the two principal investigators of the project, Prof David Hesmondhalgh and Dr Hyojugn Sun back in April and will start releasing the findings and the data in July 2021.

Justified and Unjustified Differences in Earnings

Stating that the greatest difference among rightsholders’ earnings is related to the popularity of their works and recorded fixations can appear banal and trivial. Yet, because many payout problems appear in the hard-to-describe long tail, understanding the justified differences of rightsholder earnings is an important step towards identifying the unjustified differences. It would be a breach of copyright law if less popular, or never played artists, would receive significantly more payment at the expense of popular artists from streaming providers. The earnings must reflect the difference in use and the economic value in use among rightsholders.

In our analysis we quantify differences using the actual data of the CEEMID-CI Streaming Indexes, created from hundreds of millions of data points, and computer simulations under realistic scenarios.

Justified Difference & Changes Over Time

Among the justified differences we quantify four objective justifications:

The variability of the domestic price of a stream over time shows a diminishing, but variable value of streams. Depending on the release date of a recording, and how quickly it builds up or loses the interest of the audience, the same number of streams can result in about 28% different earnings. In the period 2015-2019, later releases were facing diminishing revenues on streaming platforms.

The variability of international market share and international streaming prices in International Competitiveness. Compared to UK streaming prices, most international markets, particularly emerging markets, have a much greater variability of streaming prices. The variability of prices in advanced foreign markets such as Germany was similar to that of the British market, but in emerging markets and smaller advanced markets–such as the Netherlands–we measured a variability of around 50-80%. Artists who have a significant foreign presence, depending on their foreign market share, can experience 2-3 times greater differences in earnings than artists whose audience is predominantly British.

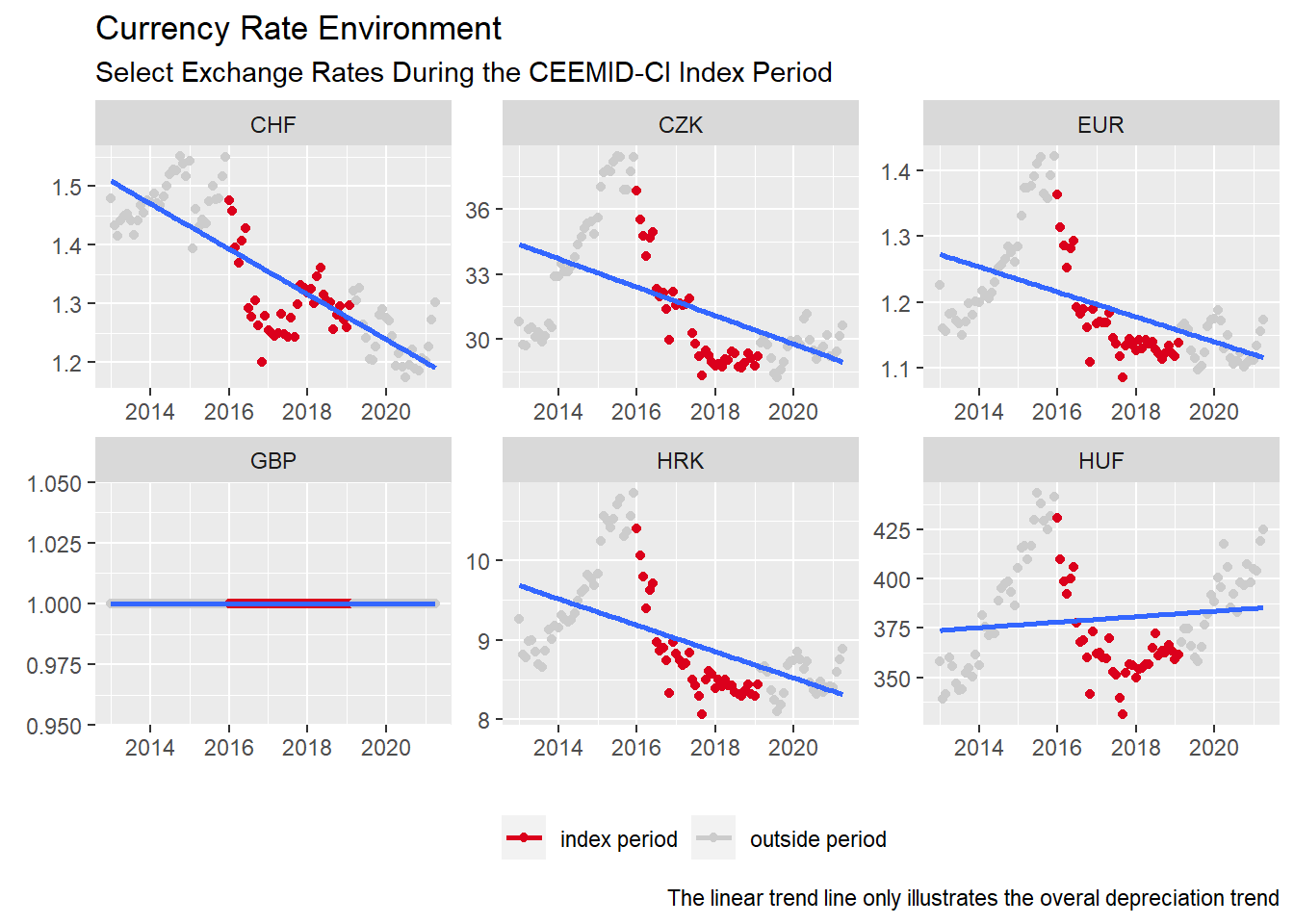

The variability of the exchange rate that is applied when translating foreign currency revenues to the British pound in Exchange Rate Effects. Our CEEMID-CI Streaming Indexes index covers the post-Brexit referendum period, when the British pound was generally depreciating against most currencies. This resulted in a GBP-denominated translation gain for artists with a foreign presence. We show that the variability of the GBP exchange rates can add bigger justified differences among rightsholders’ earnings than the entire British price variation. The exchange rate movements are typically in the range of 30%, or at the level of the British domestic price variations in streaming prices. In our simulated results, this effect shielded the internationally competitive rightsholders from a significant part of the otherwise negative price change in foreign markets.

We were also investigating the choice of distribution model. , i.e., Both models, the currently used pro-rata model and the user-centric distribution, which has many proponents (and was introduced by SoundCloud in 2021), changes the earnings of artists. We think that both models represent a bad compromise, but they are legal, and a change of zero-sum distribution change could potentially increase the income of less popular and older artists at the expense of very popular and younger artists. More about this in our forthcoming report!

In our understanding, there are some known and some hypothetical causes of unjustified earning differences.

We did not have systemic data on the uncollected revenues–these are earnings that are legally made, but due to documentation, matching, processing, accounting, or other problems, the earnings are not paid. We could not even attempt to estimate this problem in the absence of relevant British empirical data. The problem is likely to be greater in the case of composers than in producer and performer revenues. In ideal cases, of course, the unclaimed royalty is near 0% of the earnings; it seems that on advanced markets the magnitude of this problem is in the single digits, and in emerging markets much greater, sometimes up to 50%. Royalty distribution is a costly business, and the smaller the revenue, the smaller the cost base to manage billions of transactions and related micropayments. We are working with a large group of eminent copyright researchers to understand this program better and provide regulatory solutions. See Recommendation Systems: What can Go Wrong with the Algorithm? - Effects on equitable remuneration, fair value, cultural and media policy goals

More analysis is required to understand how the algorithmic, highly autonomous recommendation systems of digital platforms such as Spotify, YouTube, Apple, and Deezer, among others, impact music rightsholders’ earnings. There are some empirical findings that suggest that such biases are present in various platforms, but due to the high complexity of recommendation systems, it is impossible to intuitively assign blame to pre-existing user biases, wrong training datasets, improper algorithm design, and other factors. We are working with our data curators, competition economist Dr Peter Ormosi, antropologist and data scientist Dr Botond Vitos and musicologist Dominika Semaňáková - We Want Machine Learning Algorithms to Learn More About Slovak Music to understand what can go wrong here (see Trustworthy AI: Check Where the Machine Learning Algorithm is Learning From).

There is always a hypothetical possibility that organizations with monopolistic power try to corner the market or make the playing field uneven. The music industry requires a permanent market monitoring facility to win fights in competition tribunals, because it is increasingly disputing revenues with the world’s biggest data owners. We are working with our data curators, competition economist Dr Peter Ormosi and copyright lawyer dr Eszter Kabai - New Indicators for Royalty Pricing and Music Antitrust to find potential traces of an uneven playing field (see: Music Streaming: Is It a Level Playing Field?.)

Solidarity & Equitable Remuneration

Equitable remuneration is a legal concept which has an economic aspect. In international law, it simply means that men and women should receive equal pay for equal work. Within the context of international copyright law, it was introduced by the Rome Convention, and it means that equitable remuneration means the same payment for the same use, regardless of genre, gender or other unrelated characteristics of the rightsholder.

While the word equitable in everyday usage often implies some level of equality and solidarity, in the context of royalty payments, these terms should not be mixed.

Solidarity is present in many royalty payout schemes, but it is unrelated to the legal concept of equitable remuneration. Music earnings are very heavily skewed towards a small number of very successful composers, performers, and producers. The music streaming licensing model has little elements of solidarity, unlike some of the licensing models that it is replacing–particularly public performance licensing. However, in those cases, the solidarity element is decided by the rightsholders themselves, and not by external parties like radio broadcasters or streaming service providers.

The so-called socio-cultural funds that provide assistance for artists in financial need must be managed by rightsholders, not others, and the current streaming model makes the organizations of such solidaristic action particularly difficult. Our data curator, Katie Long is working on us to find metrics and measurement possibilities on solidarity among rightsolders.

The Size of the Pie and the Distribution of the Pie

The current debate in the United Kingdom is often organized around the submission of the #BrokenRecord campaign to the DCMS committee, which calls for a legal re-definition of equitable remuneration rights4. This idea is not unique to the United Kingdom, in various European jurisdictions, performers fought similar campaigns for legislation or went to court, sometimes successfully, for example, in Hungary.

Another hot redistribution topic is the choice between the so-called pro-rata versus user-centric distribution of streaming royalties. We think that both models represent a bad compromise, but they are legal, and a zero-sum distribution change could potentially increase the income of less popular and older artists at the expense of very popular and younger artists. We instead propose an alternative approach of artist-centric distribution that could be potentially a win-win for all rightsholder groups; further elaboration of the concept lies outside the scope of this report.

Our mission with the Digital Music Observatory is to help focus the policy debate with facts around the economics of music streaming. The legal concept equitable remuneration is inseparable from the economic concept of fair valuation, and music streaming earnings cannot be subject to a valid economic analysis without analyzing the economics of music. Streaming services are competing with digital downloads, physical sales, and radio broadcasting; and the media streaming of YouTube and similar services is competing with music streaming, radio, and television broadcasting as well as retransmissions. It is a critically important to determine if in replacing earlier services and sales channels, the new streaming licensing model (a mix of the mechanical and public performance licensing) is also capable of replacing the revenues for all rightsholders.

The current streaming licensing model in Europe is a mix of mechanical and public performance rights. Therefore, when we are talking about music streaming, we must compare the streaming sub-market with the digital downloads, physical sales and private copying markets (mechanical licensing), and with the radio, television, cable and satellite retransmission markets (public performance licensing.) Our experience outside the UK suggests that these replacement values are very low.

Join us

Join our open collaboration Economy Data Observatory team as a data curator, developer or business developer. More interested in environmental impact analysis? Try our Green Deal Data Observatory team! Or your interest lies more in data governance, trustworthy AI and other digital market problems? Check out our Digital Music Observatory team!

Footnote References

state51 Music Group. 2020. “Written Evidence Submitted by The state51 Music Group. Economics of Music Streaming Review. Response to Call for Evidence.” UK Parliament website. https://committees.parliament.uk/writtenevidence/15422/html/. ↩︎

Artisjus, HDS, SOZA, and Candole Partners. 2014. “Measuring and Reporting Regional Economic Value Added, National Income and Employment by the Music Industry in a Creative Industries Perspective. Memorandum of Understanding to Create a Regional Music Database to Support Professional National Reporting, Economic Valuation and a Regional Music Study.” ↩︎

Antal, Daniel. 2021. “Launching Our Demo Music Observatory.” Data & Lyrics. Reprex. https://dataandlyrics.com/post/2020-09-15-music-observatory-launch/. ↩︎

Gray, Tom. 2020. “#BrokenRecord Campaign Submission (Supplementary to Oral Evidence).” UK Parliament website. https://committees.parliament.uk/writtenevidence/15512/html/. ↩︎